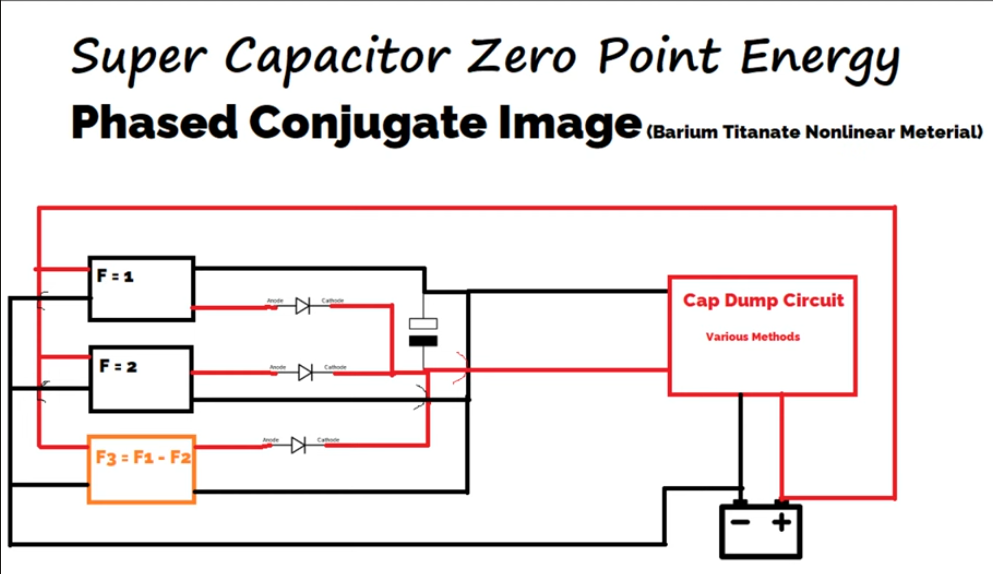

Phased-Conjugate Image Powering with a Ferroelectric Capacitor (Four-Wave Mixing in Practice)

A clear, hands-on explainer of the “phase-conjugate replica image” idea often associated with Tom Bearden—refined here into a practical four-wave mixing (FWM) experiment using a ferroelectric capacitor (e.g., barium-titanate based). We’ll cover what it is, why three injected tones are required, and how to probe for a “sweet spot” where the device appears to deliver a stronger discharge than the charge you supplied.

F1 and F2, plus a seed at F3 = F1 − F2, all injected into a nonlinear (ferroelectric) capacitor.

The medium produces a conjugate (fourth) wave internally. A “cap-dump” stage harvests the pulses.

Safety & Scientific Honesty

- Use low voltages while exploring (bench supplies, function generators). Add fuses and current-limits.

- Claims of “overunity” are hypotheses here. Do full power accounting: measure instantaneous

V×Iinto and out of the device and integrate over time. - Not all “supercapacitors” use barium titanate. For strong nonlinearity, use a ferroelectric/ceramic capacitor (BaTiO3 or similar) or a supercap specifically built with a ferroelectric composite.

1) The Core Idea, Cleaned Up

- Nonlinear medium: A ferroelectric dielectric (e.g., barium titanate) is strongly nonlinear. When driven with multiple tones, it mixes them.

- Bearden’s step (two tones): Drive with

F1andF2. The medium generates a difference-frequency component (F1 − F2) among others. - The missing step (seed tone): Inject a third tone

F3that equals the expected difference (F3 = F1 − F2) and is phase-aligned. This “seeds” the nonlinear process. With all three present, the medium can form a strong phase-conjugate replica (the fourth wave) that returns energy coherently. - Why ferroelectric capacitors: They already store charge and sit between your sources and the load; the emerging conjugate wave interacts inside the dielectric, so you avoid complicated external feedback networks.

2) Lab Setup

Instruments

- Two function generators with phase-lock (or one dual-channel generator): produce

F1andF2. - Third generator or synthesized output for

F3 = F1 − F2(can be derived in the same instrument if it allows internal mixing). - Digital scope (2–4 channels), current shunt (low-ohm), and a precise DMM.

Device Under Test (DUT)

- Nonlinear cap: a BaTiO3 ceramic/ferroelectric capacitor or a composite “supercap” known to include ferroelectric material.

- Injection network: series resistors (to prevent source fighting), small signal diodes (optional) to steer paths, and a star ground/reference node.

- Cap-dump: a synchronous MOSFET or SCR dump (with diode) into a storage element (e.g., a low-ESR electrolytic or a small battery) for pulsed extraction.

3) Frequencies, Phases, and Levels

- Start band: Explore roughly

10 kHz → 1 MHz. Ferroelectrics often show strong dispersion in this region—your “sweet spot” lives here. - Set pumps: Choose

F1andF2close enough thatF3 = F1 − F2is within your generator’s range (e.g., 400 kHz and 410 kHz → 10 kHz seed). - Phase-lock: Ensure

F1andF2are phase-locked. Then align the seedF3so its phase reinforces the internally generated difference component. - Amplitudes: Keep

F1andF2moderate (e.g., 1–5 Vpp each to start). Make the seedF3lower (≈10–30% of the pump amplitude).

4) Wiring (text schematic)

CH1 (F1) ──┬─[R]──► DUT (ferroelectric capacitor) ◄──[R]─┬── CH2 (F2)

│ │

└─[R]──► CH3 (F3 = F1−F2, phase-aligned) ──┘

DUT node ──► Cap-Dump (MOSFET/SCR) ──► Storage cap/battery (through diode)

Return/ground: common star point; scope uses x10 probes with short leads.

Resistors (100–1kΩ) isolate the sources so they don’t drive each other. Keep leads short; ferroelectrics can be very reactive at HF.

5) Finding the “Sweet Spot”

- Characterize baseline: With only

F1present, measure charge time and dump energy E into your storage element. Repeat forF2alone. - Two-tone mix: Apply

F1andF2(phase-locked). Sweep their frequency while monitoring any growth atF1 − F2. - Add the seed: Inject

F3 = F1 − F2. Adjust its phase until you see maximum coherent response (look for a clean, larger-than-expected pulse at the dump node). - Tune for peak: Nudge all three frequencies together (keeping

F3equal to the difference). You are hunting for a point where the DUT’s effective behavior looks “super-capacitive” (i.e., stronger discharge pulse for a given small charge input).

6) Measuring Gain Correctly

- Instantaneous power method: Record

V(t)andI(t)for each input channel into the DUT and for the dump output. ComputeP(t) = V(t)·I(t), then integrate over identical windows:E = ∫P(t)dt. - Subtract losses: Include resistive heating (series resistors), gate drive power (if any), and capacitor ESR.

- Look for artifacts: Phase errors, scope math bandwidth limits, probe ground loops, and diode recovery can all mimic “excess” energy. Verify with a second method if you see surprising results.

7) Why This Arrangement Helps

- All in one medium: The nonlinear mixing and energy storage occur inside the same ferroelectric dielectric, so the conjugate component “arrives” where it can be harvested—no lossy external feedback loop.

- Seeded FWM: Injecting the seed

F3aligns the process and can dramatically strengthen the phase-conjugate wave, compared with relying on spontaneous difference-frequency generation alone. - Cap-dump timing: By dumping on the peak of the coherent pulse, you convert reactive surges into useful DC while disturbing the mixing process as little as possible.

8) Practical Tips

- Try different ferroelectric parts (C0G/NP0 ceramics are linear—avoid; look for high-K dielectrics or explicit BaTiO3 ferroelectrics).

- Keep the DUT cool; ferroelectric properties shift with temperature. Log temp during sweeps.

- Add a narrow band-pass (centered at

F3) between the DUT node and the dump to reduce pump leakage into the storage element. - Experiment with small reverse bias on the DUT (DC offset) to pre-polarize domains and stabilize the phase alignment.

What Success Looks Like

- A narrow, repeatable pulse at the dump node that grows strongly only when all three tones are present and phase-aligned.

- Effective “apparent capacitance” increase: for the same small charge energy, you observe a disproportionately larger discharge pulse (after careful accounting).

- Robustness across repeats: moving a few kHz off the sweet spot should reduce the effect sharply—strong frequency/phase selectivity is a good sign.

If you reach this point, you’ve likely found a genuine nonlinear-mixing resonance. From there, refine the dump timing, minimize losses, and document everything.